Georgia Rowswell’s art exhibit, Textile Stories, is carefully arranged throughout all three floors of the Laramie County Library. At first glance, the pieces seem as varied as the many colors they are comprised of; there are articles of thrift store clothing hanging on each floor, small life rings displayed in glass cases, a large life ring exhibited on a wall, and a deconstructed quilt draped over the library’s gallery. The variation makes sense, seeing as Textile Stories is a compilation of four separate art projects, Crazy, Who Made My Clothes?, Leap 366, and Thrift Store Life Rings. But while the pieces and projects may appear different in format and appearance, they all have a common thread pulling them together: stories.

“Textiles are what I work with,” Rowswell says, “and textiles have stories embedded in them.”

Rowswell illustrates an example of what she means over Zoom, holding up a beautifully stitched kimono. “I bought this in Japan, and every time I look at it I remember the trip to Misawa where my son and his wife were stationed and meeting my newborn granddaughter. You can look at important clothing like a wedding dress, or not so important clothing like a t-shirt you got in Hawaii. Whatever you look at, these items are all triggers; they bring back stories.”

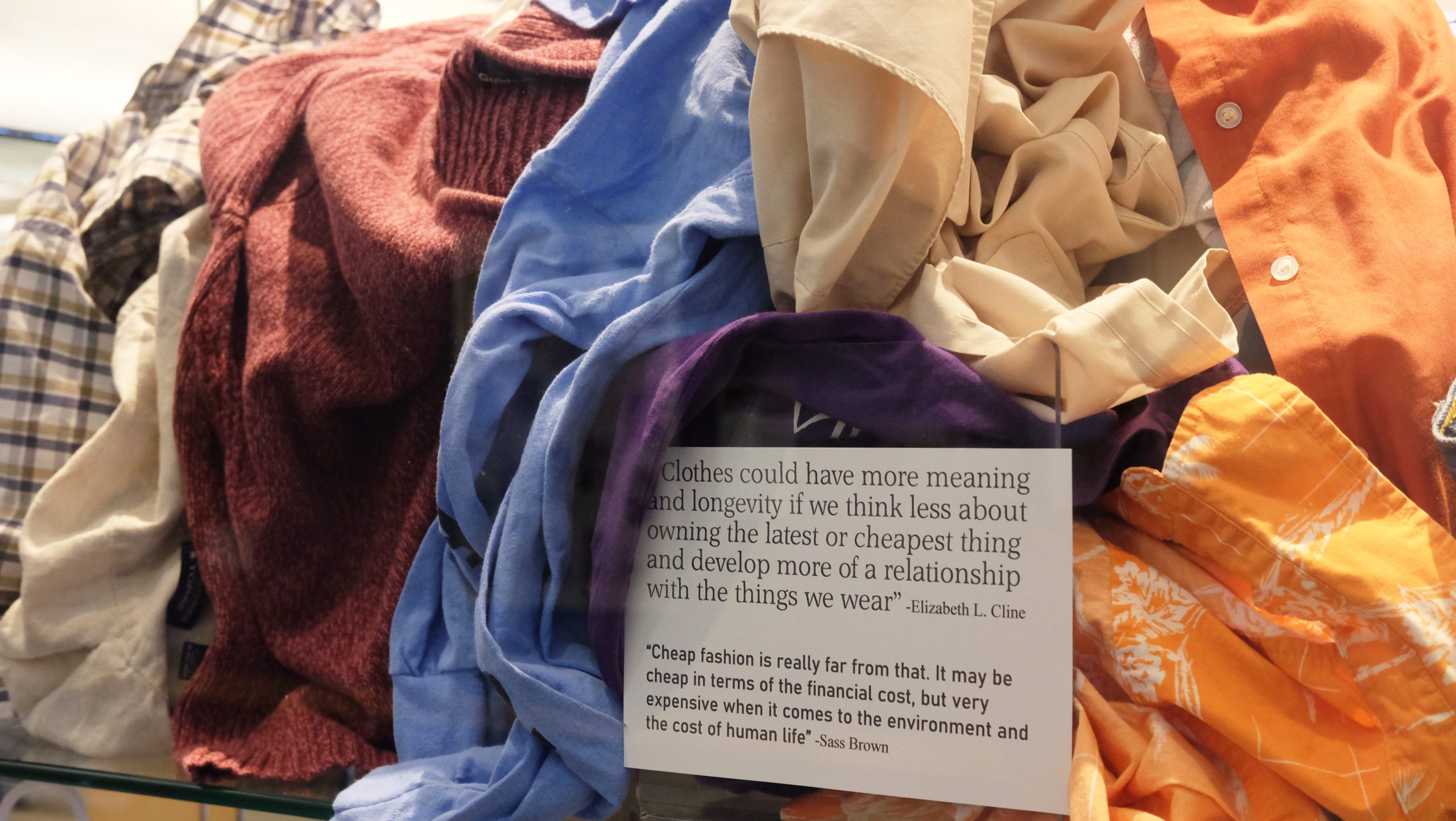

Almost every component of Rowswell’s exhibit is constructed from textiles. Her smaller life rings, resemblances of trees’ growth rings, are constructed from strips of thrift store clothing. Her Crazy quilt is stitched out of thrift store clothing as well, from shirts, pants, dresses, and more that were made in the 36 countries that export the most goods to the United States. Rowswell’s large life ring, five feet in diameter and a representation of a leap year in her life, is made from donated clothing, clothing she found from her travels, and clothing purchased at yard sales or secondhand stores. The final component of Textile Stories are the pieces of clothing displayed throughout the library with tags indicating where they were made, drawing attention to the impacts of the fashion industry.

Choosing textiles as her medium is what makes Rowswell’s art so unique, and so layered with meaning. The materials themselves are woven with stories, stories of how the piece of clothing came to Rowswell and stories of who made the piece of clothing to begin with. Rowswell reflects fondly on creating these pieces, talking about where she found specific pieces. Her stories about finding textiles range from a friend stating that the material that most represented him was “tie-dye corduroy” to someone who asked her if she could use his lone, used sock for her artwork.

In addition to the personal stories Rowswell gathers while finding materials are the universal and global stories that she hopes people will think about when looking at her artwork.

“Crazy explores global stories and deals with universal problems regarding workers’ rights across the world and the global environmental issues we all face, which makes the stories personal again. Who Made My Clothes tells global stories as well, but is also universal and personal because we all wear clothes that are touched by people around the world, people whose stories are very different from our own. We can know some of their stories if we take the time to care and understand.”

The idea of knowing someone’s story, gathering information about their background and investing time and effort in learning more about them fits perfectly within the confines of a library, a place dedicated to the continual pursuit of knowledge and the dissemination of stories. Like Rowswell’s exhibit, the library harbors personal stories, local stories, universal stories, and global stories. Like Rowswell’s exhibit, a library invites people in to consider their place in the world and their relationships to others living in it. In fact, both the library and the exhibit implore people to learn, to discover, and to think critically about the world we live in.

Rowswell’s exhibit also illuminates the many ways in which stories exist. They can live within the confines of two books covers and come to life through the words of authors, but they can also manifest themselves in other brilliant and beautiful displays. A piece of clothing can captivate a viewer, just as a carefully worded metaphor can enthrall a reader, and both demand a closer inspection, both challenge their viewers to discern the meaning that lies beneath the veneer of beautiful language and artistic renderings.

But, perhaps one of the most striking components of the exhibit, suspended within this repository of knowledge, is that both the library and the artworks do not allow viewers to simply exist as spectators; they both call the viewer to participate, to question, to consider, and to act. The books, poems, and novels on the shelves of the library require the reader to consider perspectives outside themselves; they demand that the reader engage in other worlds entirely and partake in experiences that are not their own. Rowswell’s art makes the same demand. It asks you to think about the textile worker who labored for endless hours and minimal pay to create the pieces of clothing that went into the exhibit. It encourages you to examine how the clothes you purchase impact the environment, textile workers, and the garment industry.

their own. Rowswell’s art makes the same demand. It asks you to think about the textile worker who labored for endless hours and minimal pay to create the pieces of clothing that went into the exhibit. It encourages you to examine how the clothes you purchase impact the environment, textile workers, and the garment industry.

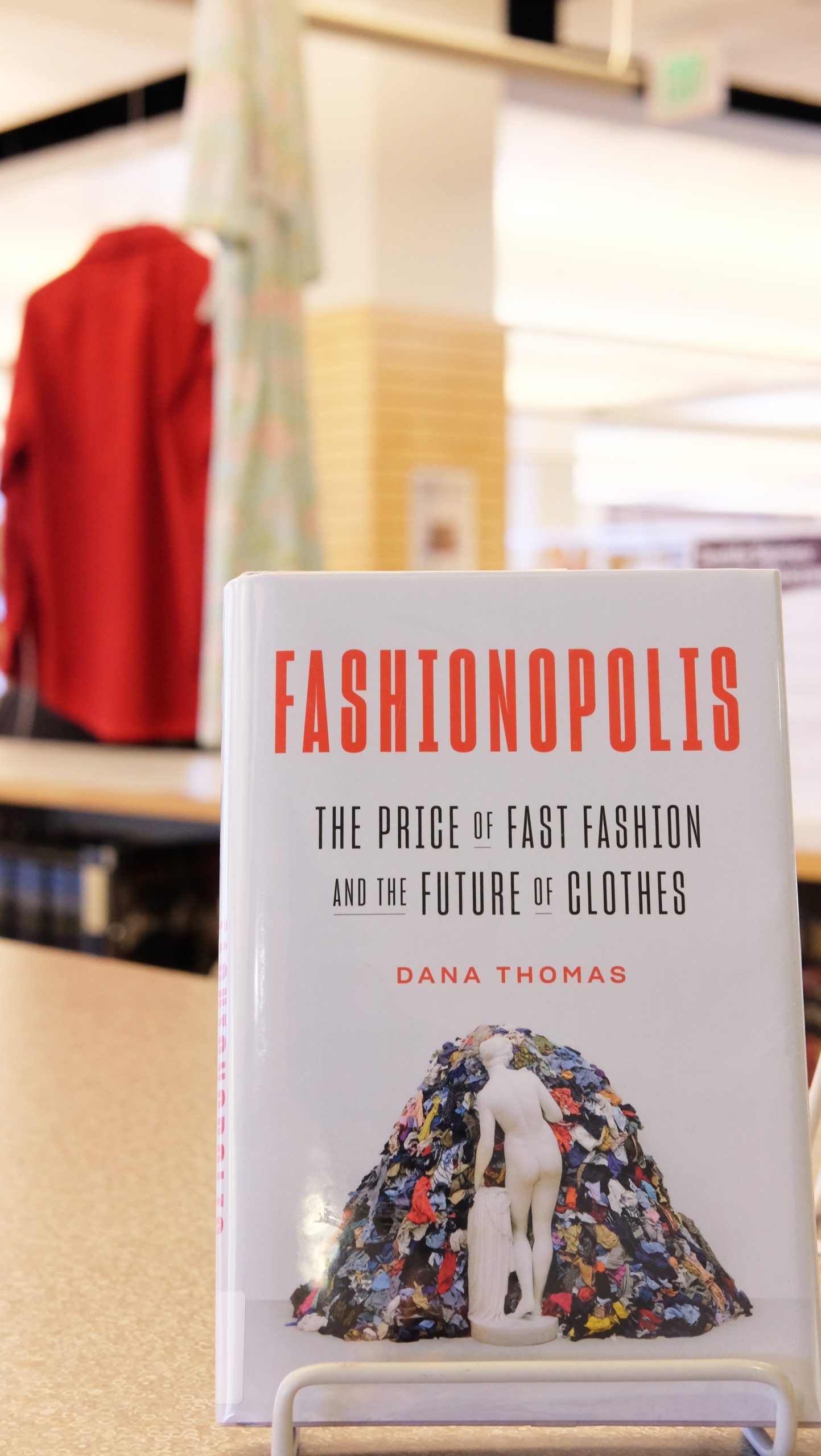

So, while it is art that hangs suspended above the library’s entrance gallery, it is also an expansion of the stories that sit on the library’s shelves. The books about fast fashion, working conditions of the global south, and reusable fashion design have spilled from the pages and into display cases. The library and Rowswell’s exhibit are showing you that stories exist everywhere you turn and that they exist in many facets, facades, and formats. The library and the exhibit are showing you that you can learn from all of these stories, should you only take the time to read them.

This is what Rowswell hopes people take away from the exhibit–a desire to discover more stories about the people who made the hanging, stitched, and sculpted clothing.

This is what Rowswell hopes people take away from the exhibit–a desire to discover more stories about the people who made the hanging, stitched, and sculpted clothing.

“I would encourage people to go home, look at some labels in their clothing, get familiar with them and then maybe pick one country and learn something about it, be curious, go to your library and get that book. The clothing industry is a big and complicated issue, but there are some companies that are doing the right thing and providing some light; making yourself aware of these is issues is part of that light. I just want to make people aware and then maybe they’ll start caring about it a little bit more.”

After all, stories are the common thread that pull the exhibit together, but they are also the common thread that pulls humanity together. They are what makes us care about the people around us. Stories weave together the rich tapestry that is human life, filling it with color and texture, making it beautiful to behold just like the shelves of a local library and the art hanging in Textile Stories.

~Kasey M.

Head to Laramie County Library any time the building is open to view Textile Stories and learn more about each piece of the exhibit. More information about Georgia Rowswell, her creative process, and other works can be found on her website: https://www.georgiarowswell.com/

Click here for research resources about the garment industry.